Events

Workshop 3

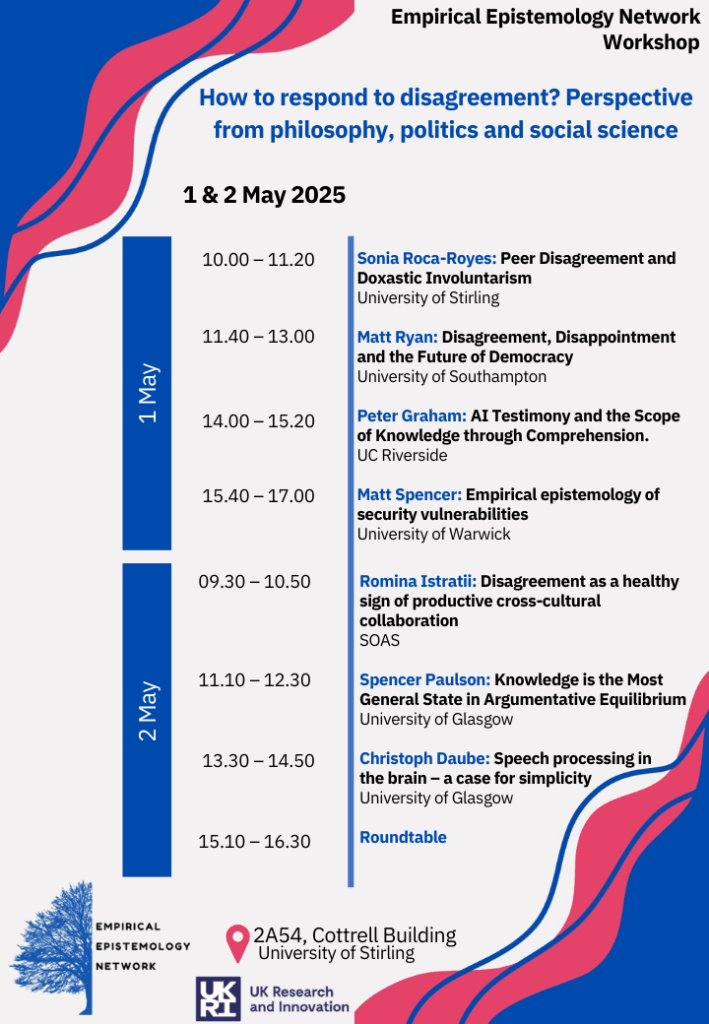

How to respond to disagreement? Perspective from philosophy, politics and social science.

1 & 2 May 2025

2A54, Cottrell Building, University of Stirling

Speakers

Epistemologists:

- Peter Graham (UC Riverside)

- Sonia Roca-Royes (Stirling)

- Spencer Paulson (Glasgow)

Empirical Researchers:

- Matt Ryan (Southampton)

- Romina Istratii (SOAS)

- Matt Spencer (Warwick)

- Christoph Daube (Glasgow)

Abstracts

Sonia Roca-Royes

Peer Disagreement and Doxastic Involuntarism

The talk will introduce the phenomenon of peer disagreement and a central question it raises in relation to epistemic rationality: how are we to respond, epistemically, to such phenomenon? I will survey the two views on the matter that lie on opposite ends of a spectrum and let this survey inform the motivation of a moderate answer instead, whose distinctive feature is that it takes seriously the hypothesis of doxastic involuntarism.

Matt Spencer

Empirical epistemology of security vulnerabilities

I’d like to think about the empirical epistemology of cyber security vulnerabilities. These flaws can be highly consequential, and their discovery can render security claims false or uncertain, creating the possibility of digital systems and devices operating in ways dramatically different from what is expected and intended.

Most security vulnerabilities are coding errors, but there is an also an important category that can be exploitable even in cases where there are no bugs in the software. What I have in mind are hardware vulnerabilities, and in particular software-induced hardware vulnerabilities such as Rowhammer (a vulnerability in Dynamic Random Access Memory) and transient execution vulnerabilities such as SPECTRE and Meltdown (vulnerabilities in processor design).

In my talk I will introduce hardware vulnerabilities (in an accessible manner), and then focus our attention on a number of claims that we might be interested in analysing further:

- Statements about functional features of the hardware, in documentation or patents, that tip off vulnerability researchers, so that they start experimenting in ways that, in some cases, end up with the discovery of an exploitable flaw.

- Derivative ‘trigger’ statements that make vulnerabilities public prior to their official disclosure, such as reports on experimental results, discussions on open source mailing lists or technology journalism.

- Claims made by vendors relating to the nature of the problem, such as Intel’s incendiary press release, on the day when the Meltdown and SPECTRE bugs were publicly announced, that the ‘computing devices’ in question were ‘operating as designed’.

- Claims made by hardware manufacturers that the issue is fixed in their products (for instance in newer generations of products), that later turn out to be incorrect because the vulnerability was deeper or more slippery than had been recognised.

As a sociologist, I am interested in how normative expectations are performed: how the ‘proper’ functioning of technology is defined, and redefined in interaction and social process.

Peter Graham

AI Testimony and the Scope of Knowledge through Comprehension

Spencer Paulson

Knowledge is the Most General State in Argumentative Equilibrium

I argue that knowledge plays a distinctive role in psychological explanation that weaker epistemic states cannot because knowledge is the most general epistemic state that is robust in the face of counterevidence. I go further than previous advocates of this view, however, and claim that being robust in the face of counterevidence makes your belief robust in the face of counterargument. Drawing on recent work on the “social intentionality hypothesis”, I argue that this makes knowledge uniquely well-suited to facilitate epistemic social coordination. Since executive-level belief revision involves running offline simulations of epistemic social coordination, knowledge plays an explanatory role in executive-level belief revision as well. Assigning this explanatory role to knowledge allows us to see its importance while sidestepping some points of contention such as whether knowledge is analyzable and whether it is a (non-composite) mental state.

Romina Istratii

Disagreement as a healthy sign of productive cross-cultural collaboration: The need for articulating an epistemology of disagreement in international gender and development work

In the past four years, I have led Project dldl/ድልድል, which seeks to respond to domestic violence in Africa and Europe in culturally sensitive and theologically grounded ways informed by a decolonial ethos. The project has aimed to bridge secular and religious frameworks of understanding and responding to domestic violence to promote integrated and collaborative approaches between statutory, feminist and faith-based institutions and initiatives. I established the project in response to a persistent neglect in mainstream GBV responses to engage genuinely and productively with tensions that often emerge between secular gender standards promoted through a human rights discourse (often understood and perceived as universal or superior) and the norms and ideals of culturally diverse and religious communities around the world. Our work is precisely centred on the ethical and epistemological tensions between these worldviews, and recognises that both secular and religious discourses can be instrumentalised to perpetuate domestic violence and women’s abuse, that perceived tensions must be given due recognition and navigated with sensitivity to minimise unnecessary backlash given colonial histories, and that appreciating people’s cultural and religious worldviews is a necessary condition for respecting difference, but this should not hinder us from challenging harmful understandings, attitudes and norms. In my presentation, I will discuss the importance of cross-cultural awareness and literacy, decolonial reflexivity and Socratic dialectics in navigating positions that may seem to be or are incommensurable and how we can work productively within cross-cultural differences. While typically the aim has been to resolve disagreement, I would like to argue that disagreement is a healthy sign of genuinely embracing difference and diversity in the world. Existing within and despite disagreement might be necessary for responding collaboratively to societal challenges of a cross-cultural nature, raising the need for articulating an ‘epistemology of disagreement’ in international gender and development work.

Christoph Daube

Speech processing in the brain – a case for simplicity

As neuroimaging matures, there is an expectation that ever more elaborate cognitive processes will be matched to corresponding neuronal measurements recorded with techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging or magnetoencephalography (MEG). Correspondingly, it seems intuitive that increasingly intricate operationalisations of e.g. linguistic structures are reported to be observable in brain waves recorded during passive speech listening.

In this talk, I will take an alternative perspective: While the brain undoubtedly engages in virtually arbitrarily complex analyses of speech input, neuroimaging will only ever be sensitive to an — in a functional sense — arbitrary subset of all brain activity. I therefore propose that it is worthwhile to also pursue simpler models of neuronal measurements and see for what range of ostensibly complex neuronal response components they can account for. I will do this using two examples: Phonemes and syntactic parsing. In both cases, I will show how asserted MEG correlates thereof can also be explained using acoustic features.

To conclude, I argue that my results do not devalue reports of correspondences of complex processing — they are crucially needed as benchmarks, and I cannot provide evidence for their absence. However, I hope that my results can spark more enthusiasm for more parsimonious approaches. This should increase the balance of approaches working from both ends of the simplicity–complexity continuum. Ultimately, such a balance will deepen our understanding of how we acquire and revise beliefs about brain function.

Matt Ryan

Disagreement, Disappointment and the Future of Democracy

Democracies are in Gerry Stoker’s words ‘designed to disappoint’ (2006). This is a positive feature of democracy. If you get everything you want all the time, chances are you are living in a dictatorship. Yet most democrats do not experience disappointment positively, especially if they do not get the sense that they are ever winners in collective societal decisions. This talk will introduce a number of lessons from the Rebooting Democracy project, and try to bring them to bear on imaging a future democracy where disappointment and disagreement are experienced more positively. I will discuss why people find it so difficult to identify arguments, what effect positive framing has on political movements, how deliberation is mediated by culture and identities, and how participating in different forms of political activity affect decisions about how to resolve disagreements and when to engage with them.

Schedule

Workshop 2

The social dimension of knowledge

3 & 4 September 2024

Studio 2, Advanced Research Centre, University of Glasgow

The second workshop will focus on issues that emerge with the social dimension of knowledge acquisition and rational belief-management. They include: what is the right response to disagreement with a peer, the emergence of fake news, and the conditions under which we are warranted in accepting the testimony of others.

Speakers

Epistemologists:

- Kate Nolfi, University of Vermont

- Sven Bernecker, University of Cologne

- Sophie Keeling, UNED Madrid

- Jack Lyons, University of Glasgow

Empirical Researchers:

- Kristina Hultgren, Open University

- Constance Smith, University of Manchester

- Bodo Winter, University of Birmingham

- Viktoria Spaiser, University of Leeds

Abstracts

Sophie Keeling

Resistant reasons

Much research has centred around beliefs and actions that conflict with what are in fact good reasons. Here the archetypal case would be in in which, say, I believe that I am a kind person in spite of obvious evidence to the contrary. But we can also identify a related and under-explored phenomenon whereby what seems resistant is that one responds in some way to a particular reason or group of reasons (e.g., when I always listen to one unreliable friend whatever they say). In this talk, I will introduce the concept of resistant reasons and its applications in both philosophy of psychology and social philosophy.

Kristina Hultgren

The rise of English in non-Anglophone universities: Challenges and opportunities of transdisciplinary approaches

In this presentation I explore the challenges and opportunities of working across disciplinary and epistemological boundaries on my UKRI-funded Future Leaders Fellowship. The fellowship explores the rapid ascendance of English as an academic language in non-Anglophone European universities from a transdisciplinary perspective. Whilst the global spread of English across the world often causes debate and raises concerns about educational disadvantage, epistemic homogenization and geopolitical inequality, the fact that it has mainly been studied by linguists has limited the potential to truly understand how English is intrinsically embedded in historical, political and economic processes of colonialism and capitalism. To understand this requires transdisciplinary approaches. In my presentation, I explore how borrowing and adapting frameworks, concepts and tools from political science into linguistics will shape not only the questions we ask but also the answers we find, in this case offering new understandings of the rise of English and its underlying processes. I consider some of the challenges of working across disciplinary and epistemological boundaries, including the often-tacit assumptions of how knowledge is constructed and what counts as ‘evidence’ in different disciplines.

Jack Lyons

Language learning and the epistemology of testimony in children

Anti-reductionist theories in the epistemology of testimony claim that testimony (believing on someone else’s say-so) is a basic source of justification, not reducible to perception, induction, and the rest. One prominent argument for this is that young children have justified testimonial beliefs, even though they’re not sophisticated enough to have the kind of inductive evidence needed for a reductionist epistemology. I’ll claim that this argument only works on the assumption of a heterodox and empirically implausible view about the nature of language acquisition. On the more plausible views, anyone able even to understand testimony is already inductively sophisticated enough for a reductionist epistemology.

Viktoria Spaiser

Empirical Research on Social Change in Response to Climate Change

In my research I work on understanding empirically how rapid social change in response to the climate crisis can happen and what prevents social change. In this talk I will given an overview of my work, including empirical research on how climate protest movements are triggering normative change and how normative change can lead to social change, how moral norms can lead to behavioural changes, including political behaviour and how socio-psychological mechanisms can lead to dysfunctional responses to the climate change threat, preventing social change. I will also briefly talk about my work on the Global Tipping Points Report and the notion of negative and positive social tipping points. All this empirical research is highly normative. Which beliefs are rational or irrational when facing climate change? Which social norms are functional or dysfunctional when facing climate change? What role does morality play in finding rational responses to the climate change threat? What social change is rational in terms of serving the collective good? Is there an agreed collective good? The talk will raise these and other questions to invite feedback and discussion across disciplines.

Kate Nolfi

Exploring an Action-Oriented Approach to Understanding the Nature of Knowledge

Knowledge seems to be as good as it gets, epistemically speaking, at least when it comes evaluating individual doxastic states, considered in isolation. Indeed, it seems that a doxastic state is as epistemically praiseworthy as it can possibly be (at least when considered in isolation) if and only if it constitutes knowledge. My goal here is to begin exploring a somewhat unorthodox and distinctively action-oriented approach to understanding the nature of knowledge, one that draws inspiration from certain elements of the increasingly influential 4E paradigm in cognitive science. Put somewhat flatfootedly, the core idea animating an action-oriented approach is just that doxastic states are most illuminatingly understood functionally, as tools of a certain sort for achieving situationally-appropriate action. Accordingly, species of epistemic evaluation are properly understood in terms of and by reference to the demands of the distinctive function that doxastic states paradigmatically perform within mental economies like ours in the service of situationally-appropriate action. For a doxastic state to be as good as it gets, epistemically speaking, is just for that doxastic state to be the best possible tool for performing this action-oriented function. A doxastic state constitutes knowledge in virtue of being as praiseworthy as it could be qua the distinctive sort of action-subservingtool that it is. On the action-oriented approach, developing an account of the nature of knowledge is, in part, an empirical project: empirical inquiry both can and should inform our understanding of the distinctive function that doxastic states paradigmatically perform within mental economies like ours in the service of situationally-appropriate action. I will explore some of the ways in which certain questions about this distinctive action-subserving function inform the ultimate shape and character of an action-oriented account of the nature of knowledge. In so doing, I begin to sketch an agenda for the empirical investigation that developing an action-oriented account of the nature of knowledge will need to involve.

Constance Smith

Knowing failure after the Grenfell Tower fire

Drawing on the work of methodological theorist Celia Lury, this paper explores the Grenfell fire inquiry as a site of knowledge production; a particular kind of ‘problem space’. Grounded in anthropological theory and ethnographic research with affected communities in North Kensington, it explores how the inquiry did not only examine what failed any why in relation to the Grenfell fire, but how it established the parameters of what counted as acceptable evidence through which failure could be apprehended. These parameters were often contested by local communities: while the official inquiry sought to frame the fire as a discrete event, for residents the fire is inextricable from longer histories of housing, discrimination and gentrification. Seven years on, the fire still reverberates, its afterlife constellating with new narratives and politics that refract failure differently. In this paper, I explore how failure is never pre-known; its shape must be made to appear. As such, failure is continually interrogated and recomposed both as an object of knowledge and as an instrument for its formation.

Sven Bernecker

Epistemic Autonomy and Dependence in the Medical Context

Given the epistemic inequality between medical staff and patients, it is often rational for patients to simply defer to medical authorities. At the same time, patients have the ultimate decision-making responsibility for their own treatment. How are patients supposed to be able to make informed and autonomous choices about their treatment if they lack (adequate) understanding of the relevant medical details? I propose a strategy for reconciling epistemic autonomy with epistemic dependence.

Bodo Winter

Statistical rituals and the generalizability crisis

The 20th century saw a major shift in the way science was conducted, with a dedicated move towards the adoption of statistical methods. The particular type of statistical methodology that has emerged as dominant over the course of the 20th century is the deeply ritualized tradition of ‘null hypothesis significance testing,’ which despite incessant calls for replacement continues to be the status quo in almost all fields, from psychology over linguistics to many of the ‘hard’ sciences. Many have pointed out that the incentive system surrounding significance tests — seeking significant results — is one factor that has brought us into the replication crisis (many findings previously held to be true failed to replicate). In this talk, I will argue that significance tests have also been instrumental in luring us into what Yarkoni (2020) has called the “generalizability crisis”: many findings fail to generalize because they do not adequately model important sources of variation in the data. I will argue that Bayesian approaches to statistical analysis provide substantial benefits for counteracting the generalizability crisis, and furthermore provide a path out of deeply ritualized statistical traditions.

Schedule

To facilitate in-person attendance at our events, we offer financial assistance for travel, childcare, etc., to people who might need it. For more information, please see the Equality, Diversity, & Inclusion page.

Workshop 1

Acquiring and losing knowledge

23 & 24 April

Cottrell Building C.3A142, University of Stirling

The first workshop will focus on the nature of knowledge, its difference from mere opinion, how it can be acquired and lost, its relation with the notions of evidence, truth and reliability of information sources.

Speakers

Epistemologists:

- Peter Graham, University of California Riverside

- Claire Field, University of Zurich

- Ema Sullivan-Bissett, University of Birmingham

- Jesper Kallestrup, University of Aberdeen

Empirical Researchers:

- Joseph Lindley, Lancaster University (Design Research)

- Luisa Enria, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (Anthropology)

- Wataru Uegaki, University of Edinburgh (Linguistics)

- Anastasia Shesterinina, University of York (Comparative Politics)

Abstracts

University of Zurich

The Value of Level-Incoherence for Avoiding Knowledge Loss

Level-coherence is a particular kind of harmony between our beliefs about what we ought to do and believe, and what we actually do and believe. Level-coherence has traditionally been thought irrational. Here, I argue that this is a mistake. I show how in a specific set of epistemic environments – those in which it is particularly easy to acquire justified false beliefs about normative requirements of epistemic rationality – level-incoherence is the rationally dominant strategy, primarily because of the role it plays in helping us avoid knowledge loss. I argue that successfully accommodating the epistemic value of level-incoherence in these environments means avoiding thinking of level-coherence as required of rationality. I suggest that instead, we should think of the apparent tension involved in level-incoherence as a defeasible reason to undertake further inquiry.

London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Indigenous Knowledge in Epidemic Response: Between Integration and Incommensurability

Recent health emergencies, from the 2014-16 West African Ebola outbreak to the recent COVID-19 pandemic, have highlighted the limitations of purely biomedical responses that do not take into account the knowledge and experiences of communities affected by epidemics. This has resulted in increased efforts to develop ‘integrated’ approaches to epidemic response—which include multidisciplinary teams and efforts to directly engage communities in epidemic responseIn this paper, I focus on the challenges that emerge when, during these integrative efforts, different notions of what constitutes ‘evidence’ confront each other in seemingly irresolvable ways. Drawing on long-term ethnographic fieldwork in Sierra Leone, I explore this question through the case of traditional healers and efforts to bring them into epidemic response activities. I firstly trace how healing knowledge is acquired and transmitted, teasing out what forms of evidence are generated as well as how they are internally and externally contested. I then consider how integrative efforts have led to erasure or loss of knowledge through assimilation, but also how everyday encounters in the field show much more complex negotiations. The paper finally raises key questions on the possibilities and limits of integration and the implications of considering incommensurability between ways of knowing.

University of Aberdeen

Digitally Extended Knowledge

The hypothesis of extended cognition says that mental processes or states extend to include extra-organismic parts of the external world, provided certain conditions on cognitive integration are met. Moreover, if knowledge is assumed to be a mental state, knowledge is by a similar line of reasoning, equally extended. However, extended knowledge presents additional challenges to do with cognitive bloat, given that knowledge is widely regarded as a distinctive cognitive achievement, for which special credit is due. This paper explores the idea that Dropbox, Google, or Wikipedia, rather than external resources, may serve to extend knowledge beyond our bodily boundaries, and if so whether this new hypothesis of digitally extended knowledge leads to any untoward expansion of knowledge.

University of York

Ethnographic surprises as a source of innovation in collective action research

This chapter draws on eight months of immersive field research with Abkhaz participants and non-participants in the Georgian-Abkhaz war of 1992-1993 to explore the value of ethnographic surprises as a source of innovation in the processual analysis of collective action. It situates the contribution in the interpretive tradition where unanticipated insights that generate changes in research designs are recognized as a major part of the research process and develops a particular notion of ethnographic surprises as unexpected narratives and observations that emerge systematically through fieldwork but are unaccounted for by existing theories. Viewed in this way, ethnographic surprises shaped both my research question and theoretical framework and enabled my core contributions to the study of mobilization in civil war—challenging the dominant assumption of potential participants’ knowledge of risk involved in mobilization and placing intense uncertainty that ordinary people experience when violence breaks out in their communities at the centre of analysis. This analysis has implications for our understanding of the broader process of mobilization and specific mechanisms that help individuals navigate uncertainty to make a range of mobilization decisions at the war’s onset. It demonstrates the potential of careful attention to participants’ own perceptions of their lived reality to advance knowledge of the processes of collective action.

University of Birmingham

Monothematic Delusions are Misfunctioning Beliefs

Monothematic delusions are bizarre beliefs which are often accompanied by highly anomalous experiences. For philosophers and psychologists attracted to the exploration of mental phenomena in an evolutionary framework, these beliefs represent—notwithstanding their rarity—a puzzle. A natural idea concerning the biology of belief is that our beliefs, in concert with relevant desires, help us to navigate our environments, and so, in broad terms, an evolutionary story of human belief formation will likely insist on a function of truth (true beliefs tend to lead to successful action). Monothematic delusions are systematically false and often harmful to the proper functioning of the agent and the navigation of their environment. So what are we to say? A compelling thought is that delusions are malfunctioning beliefs. Compelling though it may be, I argue against this view on the grounds that it does not pay due attention to the circumstances in which monothematic delusions are formed, and fails to establish doxastic malfunction. I argue instead that monothematic delusions are misfunctioning beliefs, that is, the result of mechanisms of belief formation operating in historically abnormal conditions. Monothematic delusions may take their place alongside a host of other false beliefs formed in difficult epistemic conditions, but for which no underlying doxastic malfunction is in play.

University of Edinburgh

The question-orientation of knowing, caring, and wondering

In this talk, I will discuss the semantics of various attitudinal predicates such as “know”, “care” and “wonder” from a linguistic perspective. In particular, I will defend the position that these predicates in general are question-oriented. That is, their semantic argument is a question (modelled as a set of propositions) rather than a proposition simpliciter. I will defend this position based on two main arguments: (a) when epistemic predicates (such as “know”, “forget” and “remember”) and Predicates of Relevance (such as “care”, “matter” etc.) take an interrogative complement (such as “who will call”), their interpretations cannot be reduced to declarative-embedding counterparts of the form “x knows/forgot/remembers/cares that p”, where p is a propositional answer to the interrogative; (b) taking the question-oriented semantics allows us to have a straightforward explanation of the selectional restrictions of predicates like “wonder” and “believe”, i.e., the fact that they are compatible with only a certain type of complement.

University of California, Riverside

Can Testimony Generate Warrant?

Our folk epistemology holds that neither memory nor testimony can generate propositional justification, but only functions to preserve it either overtime or between persons. But I’m committed to a view where it is possible for testimony to generate propositional warrant. This talk reviews the existing debate and reports to provide examples, where both sides of the debate should be willing to grant the possibility that testimony can generate new propositional warrant.

Lancaster University

Design, Research, and the Craft of Intermediate Knowledge

The practices of design and research come together in many ways under the banner Design Research. For example, researchers study designers to understand the nature of their professional creative practice. Similarly, designers do research to understand their clients’ needs and what they need to design. Finally, the process of designing, in and of itself, can simultaneously be a creative and a research activity. This mode of Design Research leverages the cognitive, practical, and inquiring aspects of design processes to not only produce a tangible outcome (i.e., a ‘design’) but also to produce new insights about the world (i.e., ‘knowledge’).

The nature of the knowledge produced by design is empirical—it arises directly from the observation and experience of designing as opposed to theory. However, given knowledge emerging from design tends to arise from ultimately particular design instances, it is hard to argue it is verifiable. Rather, this is a type of ‘intermediate level’ knowledge. Intermediate level knowledge aspires to be relevant and generative across different contexts but is overtly different from the universality of generalisable theories.

In this session I will use extracts from the documentary film Permission to Muck About to frame the story of Design Research’s history, present, and contemporary challenges. I will argue that the foundations of the Design Research field are, in fact, core components of most inquiry. Nonetheless, this kind of understanding is undervalued in the dominant research, innovation, and epistemological paradigm. I advocate for improved education about knowledge and epistemology from primary school onwards, to move towards a new more inclusive knowledge paradigm.

Schedule

To facilitate in-person attendance at our events, we offer financial assistance for travel, childcare, etc., to people who might need it. For more information, please see the Equality, Diversity, & Inclusion page.

Theme by the University of Stirling